Bugatti’s design director Achim Anscheidt works in Wolfsburg. On weekdays he travels by bicycle, train, or Golf GTI. But on weekends he drives his Porsche 911.

The silver Porsche rolls across the sidewalk and into a car lift with bright green lighting at the base of the building. A soft click, a hum, and the car starts ascending to the fifth floor. Here in the Berlin district of Kreuzberg, that would be enough to give it an excellent view of the city. Up on the car loft, Achim Anscheidt parks his Porsche on the loggia and turns to his other baby—a vintage vehicle that he has been restoring for ten years now. It is a Bugatti, a Type 35 from the 1920s. Anscheidt has been tracking down the original parts and fitting them together like a puzzle. It started with the ignition, wheels, and lights. He’s now at 60 percent—the drivetrain is still missing, for instance.

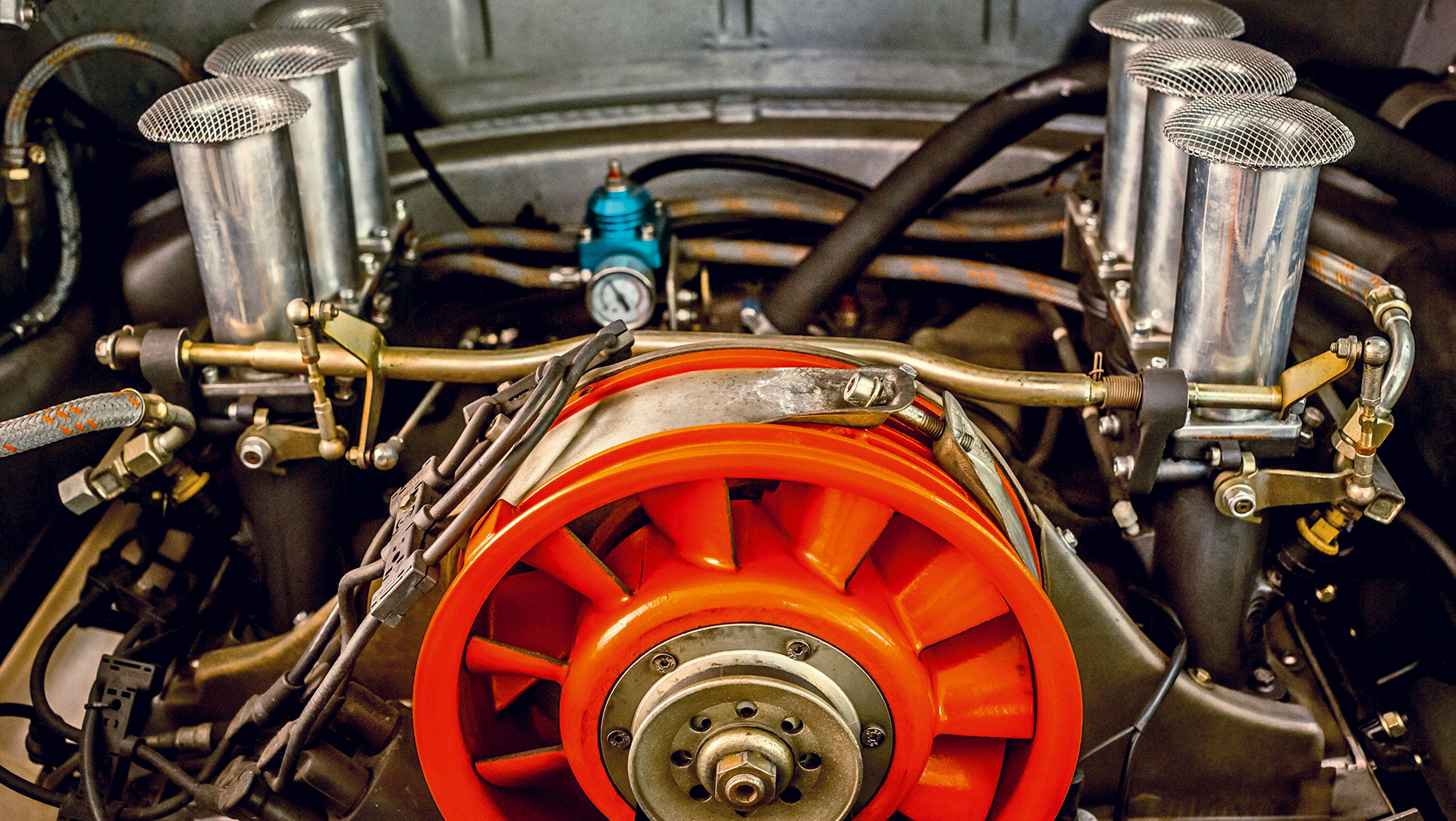

He is a well-known figure in the exclusive DIY community, and people keep an eye out for what is still needed to put the former thoroughbred racing car from Molsheim back into action. His second project is a Porsche 911 SC from 1981 that he restored together with car body maker Willi Thom in a northern neighborhood of Berlin. He stripped it and reduced it right down to the essentials. The car has no back seat, heating system, radio, or paneling. Fabric straps have replaced the door handles. Simple toggle switches operate the lights and wipers.

Lightweight materials to achieve an interesting performance-to-weight ratio

What Anscheidt finds especially appealing about his 911 is the reduction in form. “It’s been fascinating to dismantle this car a number of times, and to use only the quintessential parts in putting it back together. At some point I also grasped how you can work in targeted ways with lightweight materials to achieve an interesting performance-to-weight ratio,” he remarks. While shaping the Chiron—the fastest, most powerful, and most luxurious series-produced super sports car in the world—as the head of design at Bugatti, he was pursuing a completely different vision with his Porsche 911, which he describes as “back to the basics.” “My idea was to eliminate everything that is superfluous to the dynamics in order to attain an intriguing power-to-weight ratio.

Reduction in form: the Porsche 911

In stylistic terms the result is minimalist, and at 1,807 pounds it’s as light as my personal framework would allow. As far as the driving dynamics are concerned, it’s like a go-kart.” Anscheidt’s voice is calm, with a lightly rolling “r” that betrays his roots in the Swabian region of Germany although he spent long periods abroad and has lived for the last twelve years in Berlin’s Mitte district.

Pioneers in seeking superior power-to-weight ratios

On this Wednesday, Anscheidt is wearing Red Wing boots, jeans with the cuffs turned up, a discreetly patterned shirt, vest, and a freestyle bowtie. It’s the day of the week when he works with his team in Berlin instead of commuting to Wolfsburg on the Intercity-Express. Frenchman Etienne Salomé, the 30-something head of interior design at Bugatti, attests that his boss has a motivational leadership style, an extraordinary feel for the brand, and a “meticulous eye for detail”—which applies to his personal style as well.

Anscheidt produces a royal blue fountain pen and quickly sketches frontal views of his Type 35 and his 911 for his visitors. “Ettore Bugatti and Ferdinand Porsche were technical perfectionists. They were pioneers in seeking superior power-to-weight ratios, and in finding the sophisticated solutions to match.”

An icon of automotive engineering

Anscheidt takes a long view of design, which is essential in this particular field of work. At 53, he has been at Bugatti for twelve years. In addition to working on versions of the Veyron, he has spent ten years on what could be a second super car for Bugatti. For a while it wasn’t clear when or even if the Chiron would come onto the market. “You have to have confidence in the Group and a clear vision of the valuable substance and potential perspectives for our brand. But in contrast to mass-produced cars, a Bugatti has to be an icon of automotive engineering and still be perceived as authentic in 20, 30, or 50 years,” he says. Anscheidt had worked for Volkswagen in Spain for eight years, near Barcelona in the beautiful coastal town of Sitges, before assuming new responsibilities at the Volkswagen Advanced Design Center in Potsdam. Two of his daughters live in Spain, and the youngest is in Berlin.

The Porsche 911 in the car lift

The Chiron—which is the most valuable and powerful street-legal super sports car and which can accelerate to 300 km/h (approximately 185 mph) in 13 seconds—celebrated its premiere this past spring at the Geneva Motor Show. “These days, even we designers only rarely get a chance to test the prototype. Which is too bad, because its accelerative power is an incomparable experience even for real sports car enthusiasts.” For the Chiron, Anscheidt employed a different type of reduction program, including interpreting the old design adage of “form follows function” somewhat more strictly as “form follows performance.” As he describes it, “The major design features of the Chiron are born of technical necessity and reflect the enormous increase in power over its predecessor. This focused approach distills the sculpture of a Chiron to an authentic design statement.”

The 911 handles very directly, is incredibly agile

When Anscheidt drives his Porsche out of the garage in Berlin and onto the cobblestone streets toward Warsaw Bridge, you quickly understand what he loves about his 911. The car handles very directly, is incredibly agile, and conveys its character to the driver. “Unfortunately it spends too much time in the garage, because I only rarely get a chance to drive it during the week. And if it doesn’t see enough action, it can get a little testy,” Anscheidt sighs, as we drive pass the Kater Blau Club, which now occupies the site of the legendary Bar25.

Anscheidt’s love of his reductionist Porsche is related to a passion he pursued before becoming an automotive designer, namely, motorcycle trials. A talent for motorcycle driving clearly runs in the family; Achim Anscheidt’s father Hans Georg made a name for himself winning three world championship titles in the 1960s as a factory driver for the Suzuki company. With his father’s support, Achim started entering trials at the age of 12—and ended up winning a German junior championship title. After completing high school, he went on to display his acrobatic prowess at ever more major events, traveling throughout Europe to do so.

Designer at the Style Center in Weissach

You can get an idea of that period of his life from a 10-minute YouTube clip entitled Early Achim Anscheidt. “At first, my father was not exactly thrilled with the idea of sacrificing studies in mechanical engineering to what was essentially a circus life, but he came around once he saw the enthusiastic response to these feats.” At about the same time, Anscheidt discovered his love of design and of freehand drawing. As a result, he began studying automotive design in Pforzheim.

And what inspired him to change careers? “It was very clear to me that you can’t drive motorcycles on into old age. In my fifth semester I met Harm Lagaaij, who was the head of the Porsche design department at the time. He encouraged my endeavors, and made it possible for me to get a scholarship to the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena. Afterwards, I was able to start working as a designer at the Style Center in Weissach in 1994. I learned from the great designers of the time—an incredible experience, for which I will always be grateful to Harm.